William Phillips

William "Bill" Phillips: husband, father of four boys, lawyer & business owner, died in a plane crash in rural Alaska on August 9th, 2010. He was 56.

The small blade gleamed in the sunlight.

“What are you doing with that?” Bill asked. The question hung in the dry Colorado air as the two surveyed each other.

There was no answer from the trembling 16 year old. Just short, shallow breathing and a white-knuckle grip tightening around the pocketknife. The boy was used to being angry. Somehow or another it’s why he had been sent to Outward Bound, the adventuring and outdoor expedition group, along with a dozen other young men who were mostly, like him, from inner cities across the midwest. Like him, his peers all had some sort of record which a distant authority figure sought to correct with sore feet and campfire smoke.

And after three days of brutal hikes through Colorado’s Rocky Mountains, the boy was done with forced compliance. A pointless act of rebellion it might be, but enough was enough. He wouldn’t go quietly.

Bill broke the silence. “Look at me.” The boy paused. This wasn’t the barking command most adults gave him. This was an invitation. A teenage glare shot across the campsite at Bill Phillips, the 6’6 muscular frame and long hair casting a perfect Mountain Man. The gaze matched the tone: firm, but full of understanding and care.

“This is hard. What you’re doing is hard. I’m very proud of you for getting this far. Do you know that?”

More silence. The boy broke it this time.

“I know,” came the reply.

Bill’s piercing eyes locked on him. Then on the boy’s hand.

“You’re welcome. I need you to give me that. You’ll get it back when we get back to Denver. Promise.”

The pocketknife closed. Then after a moment, the boy casually flipped it through the air. It scattered pebbles as it landed near Bill’s feet.

“Thank you. Let’s get packed up and going.”

Bill Phillips had a way with people. He knew what motivated them, from the most vain of public officials to the most lowly parking lot attendant. He understood the importance of human tendencies like irrational fear and how it inspired short-term thinking. He knew that most people lacked the ability to accurately place themselves in the future. He intuitively mapped the ebb and flow of human cause and effect, action and reaction.

An angry, frustrated young man can only be given tough love for so long, for example. Understanding this web of human motivation and tendencies was his gift.

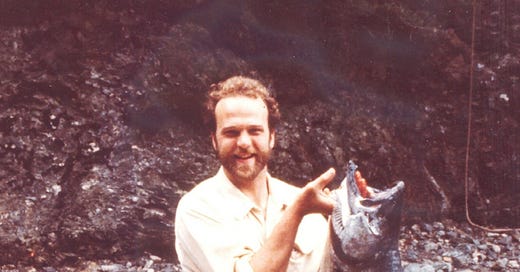

This intuition was useful to him throughout his life. Growing up in Cleveland then attending the University of Evansville on a football scholarship, he made friends easily across a wide spectrum of groups. It also contributed to his brilliant career as a lawyer and lobbyist in Washington DC. In a place where careers are often built off pretending to know where things are going, Bill stood out by being right more often than not. His career highlights included successfully lobbying for legislation protecting Native Alaskan whaling rights, guiding tech giants like Yahoo and Comcast through the early stages of the internet, and serving as a long-time staffer and confidant for Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska, the chamber’s longest-tenured Republican.

With Stevens, as it was with several key relationships in his life, his intuition also guided him on how to make a first impression. After meeting in Stevens’ Washington office and trading barbs related to a new fishing regulation (Bill had entered the commercial fishing business in Alaska after college, then moved to Washington to study law at Georgetown), the fiery Alaskan Senator thought he ended the argument by shouting, “If you’re so GODDAMN SMART, why don’t you come work for me?!”

Maybe he was simply calling the Senator’s bluff. But that’s exactly what Bill did.

He moved his law school semester to a night schedule and joined Stevens’ staff as a legislative aide. The year was 1981, and three years later he was appointed to Chief of Staff. The two men were practically inseparable following that first terse exchange. They spent their last days as they had spent so many over the years: together, enjoying the wild Alaskan country that had so enamored both of them.

Perhaps rather than stone cold intuition, Bill simply knew how to recognize opportunities and thrived on the risk/reward of bold, immediate action. Four years after joining Stevens’ staff, a beautiful aide to Minnesota Senator Rudy Boschwitz named Janet Kelly was the talk of the mostly young, single Capitol Hill staffers. Bill spotted her from across a ballroom on the night of Ronald Reagan’s second inauguration. He immediately turned to his friend Mark.

“I’m going to marry that woman.”

“Bullshit,” came the chortled reply. “A thousand bucks says you don’t even get her number.”

At their wedding two years later, Mark made a great scene of counting out ten hundred dollar bills and handing them to the happy couple.

What can I say? He had a way with people.

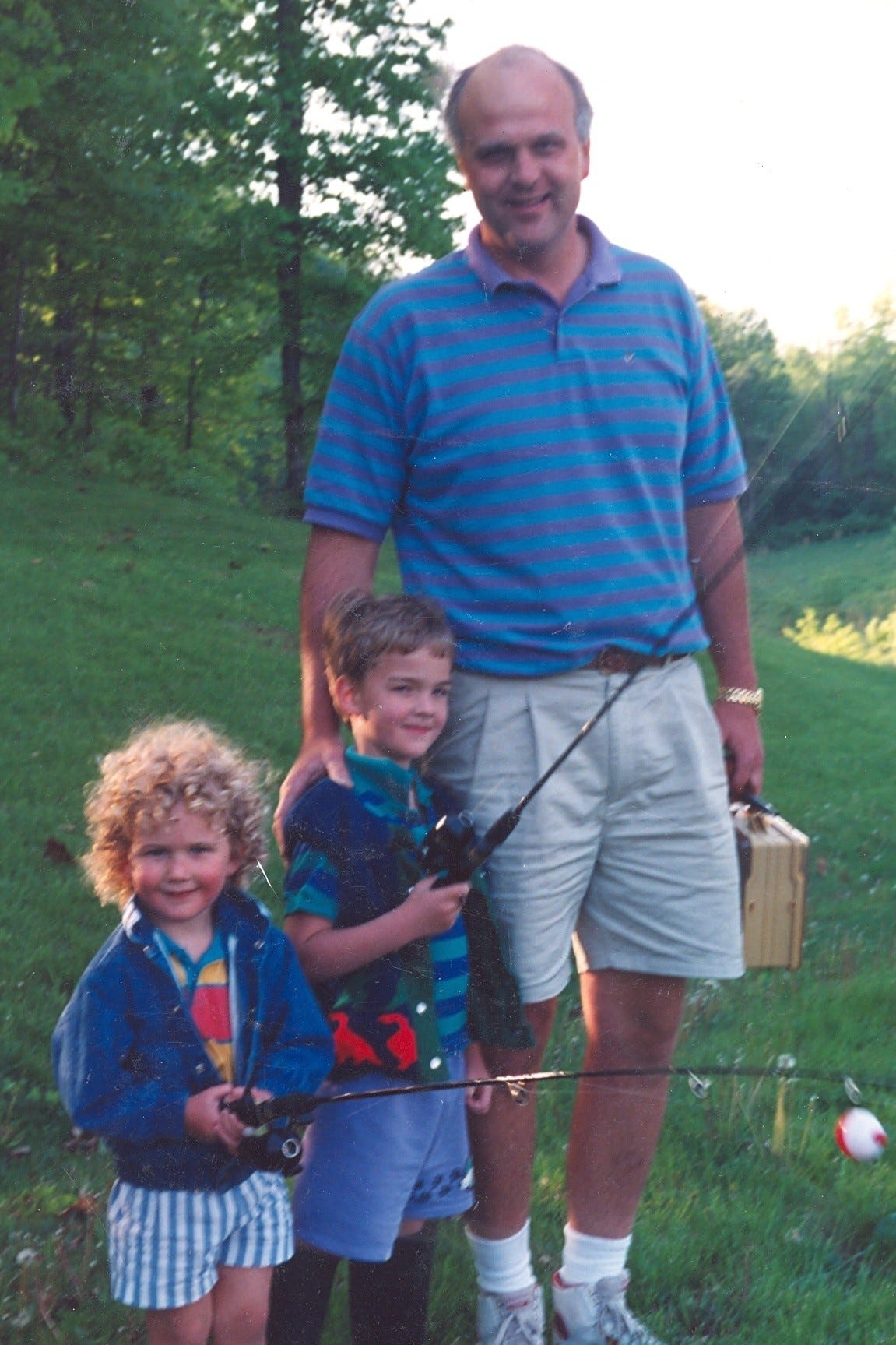

Bill and Janet welcomed their first son (yours truly) about a year later. Three more boys came over the next ten years, and their home in the countryside outside Washington gave us space to roam, break windows, and have the perfect, idyllic childhood. His favorite turn of phrase with us was “Boys, we’re going on an adventure.” And there were many, many adventures.

I can’t possibly imagine a better upbringing than the one they gave us.

Writing about him is difficult for many reasons. But the biggest reason is this: the man was an endless list of walking contradictions.

He was the hard-charging sociable football player who studied Camus and Shakespeare at Oxford. You were just as likely to find AC/DC or Dire Straits in his car CD player as you were to discover Miles Davis or Yo-Yo Ma. He was the unabashed capitalist and political apostle of the Reagan 80s who lobbied to clean oil spills and protect the dignity of Native American tribes.

There’s no easy way to put this man in a box; he spent too much of his life refusing to be placed in one.

Perhaps a lifetime of pushing envelopes and refusing categorization is what gave him courage when he needed it most. He stood by Ted Stevens’ side from his wrongful indictment through his eventual acquittal. He openly criticized the Republican-led post-9/11 movements that brought about the Patriot Act and other legislation he saw as a gross over-reach of power. I’m sure being outspoken and uncompromising cost him some invitations to cocktail parties, or maybe a few clients.

However the lesson to me and my brothers was clear: having principles that matter to you means standing firm, especially when it costs you something.

There are so many other things we learned from him.

Here are a few of my favorites:

Having proper manners doesn’t make you a snob.

If you’re frustrated or sad, get outside.

ALWAYS buy wild-caught fish.

Read the great books.

Ponder the great questions.

Reel up when setting the hook.

Spend time often with people who aren’t like you.

My dad had a way with people. He loved nature. He never abandoned his friends. He thought deeply about the kind of person he wanted to be. He was a terrible cook (but tried really hard). He loved his wife and children.

One of his friends and fishing buddies called me to catch up recently. I thought he summed my dad up pretty well.

“Man, did he know how to live.”

Andrew:

My wife Pat and I were classmates of your dad at U of E. I was also an Aces gridiron teammate of Bill’s.

I share the sentiment expressed by those that posted responses to your post. Bill was the most interesting and impressive individual I have met in my life. You have done a marvelous job using words to paint a picture of a man who excelled or learned something at from everything he attempted.

Thanks for sharing and for stimulating some enjoyable memories in my life.

Paul Swiz

Incredibly done Andrew! Thank you for sharing as we all can takeaway a lesson on “knowing how to live” from your dad. Wish I could have gotten to know him but am happy to have learned even just a little bit more thanks to this!